taking a closer look

The introduction below aims to explain how a lithograph print is created. While it is quite detailed, there are so many nuances to each step. We also aim to give you an appreciation of the difference between a hand-pulled original print and a reproduction (copy).

History

Lithography was developed in Germany by playwright Alois Senefelder (1771-1834) using limestone as the vehicle to transfer an image onto paper. It was initially used as a commercial printing process, especially for the duplication of scripts and illustrations in books. Artists realized that this medium was also an excellent way to create multiple images. Artists Delacroix and Goya, among many others, mastered the technique.

Later, painters such as Picasso, Miro and Chagall embraced lithography to create fine art. Today, hand-printed lithographs are created by artists in many parts of the world and are held in high regard as original works of art.

Definition

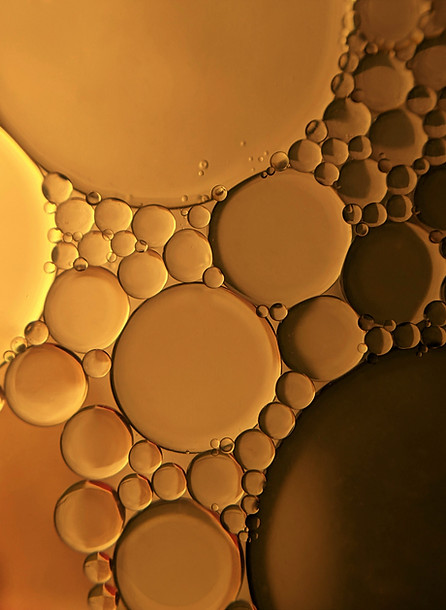

The word “lithography” comes from Greek, meaning: to write or draw on stone. Lithography is a method of planographic printing from a metal or stone surface in which the image and non-image areas are on the same plane or level, and not physically separated as is the case with other printmaking media such as “intaglio” (etching) or “relief” (woodblock). In lithography the separation of the image and non-image areas is achieved primarily through the principle that oil and water repel each other, with a chemical reaction resulting when a solution called an “etch” is applied to the stone.

Graining

Most lithography (litho) stones used throughout the world come from a quarry in Solenhofen, Bavaria, Germany, known for superior-quality limestone. A new litho stone is about 10cm thick and can be used for many years. Each image must be ground off before the next one can be drawn on the stone by using a mixture of water and an abrasive grit (carborundum). Think of sandpaper without paper.

A tool called a levigator, a spinning metal disk, is spun repeatedly across the stone until most of the water and grit are washed off. Care must be taken to know exactly when to stop grinding and refresh the stone with more water and grit. Failure to do so could severely scratch the stone which would require extra grinds to remove the scratches. Subsequent grindings with finer grit leave the stone smooth and flat in preparation for the image to be created on the stone.

In a routine graining, only about 1-2mm is removed from the top surface of the stone. Before each round of graining, it is important to ensure the stone is flat and of equal thickness on all sides. For testing the thickness, a tool called a calliper is used around the entire stone. For flatness, a metal straight edge is placed on the edge across various angles on the stone’s surface and a piece of paper (newsprint is good enough) is placed between the straight edge and the stone to indicate there is no movement and the stone is flat.

After graining is completed a rasp file is used to round off all the edges of the stone in order to prevent any buildup of ink on the edges during the processing and printing phases.

Creating the image

Each artist will have their own approach to creating an image on the stone. I usually prepare an outline drawing of the desired image on a sheet of translucent paper or mylar. Because the image on the stone must be created in a mirror image the line drawing is placed backwards and traced onto the stone. I use a sheet of newsprint smeared with red iron oxide powder, placed face down onto the stone, and then with a ballpoint pen I trace the outline drawing onto the stone resulting in a fine line outline in red oxide. This gives me a guide to complete the image based on photographs, sketches or notes I have prepared.

It is essential to scratch a small registration mark at the left and the right horizontal edge of the stone indicating the center of the drawing so that each time a drawing is transferred onto the stone in preparation for the next “run” (printing) the registration marks appear and will be used to ensure the image is aligned with the previous run. These marks are scratched into the stone with a box cutter.

Depending on the size and complexity of the image being created, this can be the most interesting but also the most time consuming phase of the entire process. The freshly ground stone is highly sensitive to grease. Anything with grease content may be used to create the image, be it liquid or a special litho pencil, similar to a fine grease pencil. Litho pencils traditionally come in a variety of grease content, from soft to hard. Even the oils on our skin may leave an impression so care must be taken not to allow the skin to come in contact with the stone while drawing.

The style of drawing, from loose to tight, will determine the type of drawing material to use. If drawing with fine detail and tone it will be necessary to keep the pencil very sharp. One way to do so is by continually filing the pencil on a sheet of sandpaper to maintain a sharp point. I often leave more pencil on the sandpaper than what I use on the stone.

.png)

Processing

Once the image is completed it must be “fixed” (stabilized) on the stone. The simple law: water and oil don't mix, the inherent sensitivity of limestone to grease, and the application of an etch to the litho stone, all combine to create the magic of lithography.

Since the image and non-image areas are on the same plane or surface, unlike other print media, they are separated on the stone using a chemical process called an etch. An etch is a solution of gum arabic and nitric acid, measured in drops of acid per ounce of gum. The formula is determined by the nature of the image and the intensity of the grease material in the image. With the application of the etch a chemical interaction occurs causing the non-image area to accept water and repel oil (litho inks are oil based) and the image area to accept oil and repel water. During the processing and printing stages water is continually sponged onto the surface of the stone between each time the stone is inked thus allowing the ink to only settle where the image is, and repelled in the non-image area.

Before the etch is applied, rosin powder is sprinkled over the image, then wiped off. A coating of talcum powder follows and is also wiped off. The rosin/talk powders are buffed down tight on the stone. This stabilizes the inked image and facilitates a smooth application of the etch solution.

The etch solution is then applied with a brush, coating the entire top surface of the stone. The image area is impervious to this application (oil and water principle) while the image area of the limestone is receptive to the solution. The etch is left on the stone for about five minutes and then removed with cheesecloth by vigorously buffing the surface of the stone leaving a thin, dry layer of the etch solution. Novice printmakers take a deep breath at the next step which involves removing the drawing material and leaving only a very faint impression of the image. This is done by pouring an oil-based solvent over the surface of the stone and rubbing it with a clean rag until the entire image is washed out. The drawing is almost invisible at this stage. Ink or another grease-based substance is rubbed into the image area creating a stain. Next, using a sponge and water, the water-soluble etch is removed.

The chemical process resulting from the application of the etch permits the image area to receive the oil-based ink and repel water. In reverse, the non-image area accepts water and repels the ink. A leather roller is “charged” (rolled) on an ink slab (a piece of plate glass where the ink is rolled out), then rolled over the surface of the stone. Rolling of ink onto the stone is repeated several times and the stone must be sponged with water between each “pass” of the roller to insure that the ink only adheres to the image. This brings back the image to its full value, and sometimes a sigh of relief.

Once the image is fully inked, the stone is allowed to dry. Another application of rosin, talcum, and etch solution follows. If the artist wishes to print more than 20 sheets of paper it is very helpful to apply several etches, as additional etches will stabilize the image which in turn will help alleviate problems during the printing phase. Processing the stone correctly is critical since any errors could destroy the image. It would then be necessary to begin again at step one - graining the stone.

.png)

Printing

A lithograph is “pulled” (printed) by pressing a piece of paper onto the stone which has been rolled with ink, transferring the ink from the stone onto the paper. Once the stone is moved onto the press bed of the printing press, the black-inked image is removed with solvent and an ink stain of the colour to be printed is applied. Even if the image is to be printed as a black and white print, the ink must be removed and replaced with a fresh stain of ink.

The etch is then washed off with a sponge and inking the image begins. A roller is rolled across an ink slab picking up ink which is then rolled onto the surface of the stone. As the stone is sponged wet between each “pass” of the roller, the damp non-image area will resist the ink and the image area will accept the ink. This procedure is repeated several times until the image is up full. Throughout the printing, a small amount of ink is repeatedly added to the ink slab to maintain consistency.

It may take several printings to get the image up to the desired quality to proceed with the printing of the edition. This is called the proofing stage. When the image meets with the artist’s satisfaction on good quality paper (usually 100% acid free) a print, called a BAT (Bon A Tirer) or RTP (Ready To Print) is set aside as a guide to maintain consistency of the printings and to know when to add ink.

When the image is fully inked, paper is placed over the image and a tympan (a sheet of plexiglass) is put on top. The press bed is cranked forward to a point where a pressure bar, containing a “scraper bar” (wooden bar with a leather strap attached to it) is pulled down onto the stone by a lever. The amount of pressure is adjusted by turning a wheel above the mechanism housing the scraper bar. Once the pressure is set, the press bed is then smoothly cranked beneath the stationary scraper bar which is greased to facilitate a smooth passage across the tympan. As the press bed carrying the stone passes beneath the scraper bar, the paper is pressed onto the stone, transferring the ink from the stone onto the paper. The pressure bar is then released, the press bed brought back to its original position and the tympan and printed paper are removed.

The stone is immediately sponged wet and the inking process is repeated; each piece of paper must be individually inked in this manner. The entire edition (number of prints pulled on good quality paper) is thus printed and left to slowly air dry on drying racks. When printing a large number it is recommended to periodically gum the stone down (sponge a layer of gum arabic over the surface of the stone) to refresh the image. This also allows the printmaker to catch their breath and take a break. If the artist wishes to call it a day and leave the printing for a later time then ink the image should be inked and a weak etch applied.

When multi-coloured lithographs are created a separate drawing must be made for each colour printed. The printing of one colour is referred to as a “run.” The stone is reground and the entire process is repeated for the next run: transferring the line drawing; drawing the image; processing; and then reprinting the same paper with the next colour.

Each piece of paper to be printed will be marked with a pencil line on the left and the right horizontal edge of the back side of the paper. The printmaker needs to line up the pencil lines with the scratches on the stone (T-Bar registration) when placing the paper onto the inked image. There are various ways to register the paper, but the T-Bar technique is less time-consuming. All my prints are created this way, even when there is only one run because it is a handy way to keep the image centred on the paper.

Editing

Once the printing is completed and the paper is dry, each print is carefully inspected for continuity of color and registration. When printing multi-colours it is usually wise to print several extra sheets of paper to allow for rejects based on color and/or registration distortions.

Traditionally, the prints are then numbered, titled and signed in pencil. The number on a print does not necessarily represent the order in which the paper was printed. When “editioning” the object is to ensure equal visual quality.

The time it takes to complete a print edition may vary from days to several weeks or months, depending on the complexity of the image and how many runs it takes to complete. Creativity, craft, care and chemistry mix in the magic of the medium that is stone lithography.